Michel Faber’s The Crimson Petal and the White tells a common tale with a not-so common twist. With “Cinderella Narratives” a dime a dozen in popular culture, it would be easy to find a film from any decade to pair with Faber’s novel. However, Pretty Woman featuring Julia Roberts and Richard Gere may be one of the best films to choose from as the female lead shares many similarities to Faber’s own Sugar. The narrative known as the “Cinderella Story” is typically that of a young woman who is the victim of a horrid circumstance who has no choice but to live her doomed life until a knight in shining armor comes along, saving her because the shoe fits. For Pretty Woman’s Richard Gere and Michel Faber's The Crimson Petal and the White, the shoe happened to be a high heel and the foot that fit it was attached to a prostitute. While the two meet their women of choice differently, and treat them quite differently, there is one moment so blatantly connecting the sources that echoes the other perfectly. Faber’s The Crimson Petal and the White follows William Rackham through his life as he falls in lust with a prostitute, Sugar, and attempts to keep his wife content so that she will play along with his charades. Though Sugar is very much in love with William and what he can do for her in her life, he turns from treating her like a partner to an employee near the end after he moves Sugar into his home as his wife falls ill. Without giving away too much about the novel’s ending, the time comes in Faber’s novel that Sugar reveals she was pregnant with William’s child. His response was to provide her with a letter of termination as his employee and a letter of recommendation (Faber 846 - 48). This is very much like the scene in Pretty Woman where Richard Gere’s character reveals to his crass lawyer that Vivian (Julia Roberts) is a prostitute. The lawyer tells Vivian that he knows what she is and proposes that they go for a romp in the hay after she is through with Gere’s character, all while the lawyer’s wife is just out of range to hear this exchange. As she discovers what Edward (Gere) has done, she is hurt by him. Later on, he makes the comment that he would like to put her up in a nice place and see her whenever he is in town. This upsets her further and in response to him pointing out that he has never treated her “like a prostitute”, Vivian remarks, “You just did.” In not fully embracing Vivian as she imagined she was being embraced, Edward and William are cut from the same cloth. Both of these scenarios represent the struggle of women as subjects to what a classmate of mine called “ the male performance”, meaning the actions men take when they perform the way society expects them to. Both male characters of significant societal reputations comment several times over on wishing they could be more involved with their ladies of the night, though they cannot be because society looks down on them. Though Faber’s novel and Pretty Woman were published just over a decade apart, the story they tell incorporates the “Cinderella Story” in unique ways. The Crimson Petal and the White offers an ambiguous ending in allowing women to move on, though it is not known if it is for the better. Pretty Woman offers ambiguity only in wondering if Julia Roberts’ character will actually go on to school to better herself now that her knight in shining armor (or rather, business man in a shiny limo) has come to “save” her. Though these romantic dramas are quite entertaining the question needs to be asked as to what is the takeaway? Have women only been able to progress as far as prostitutes turned mothers/who-knows-what from the Victorian era to the early 1990s? If so, how minuscule has the change been in the last decade compared to the last century? Though Vivian’s final line of the film redeems her by suggesting that she might have something of value to continue adding to Edward’s life, viewers do not know if her life will end up just as Sugar’s does. Arguably the best part of Faber’s novel, and what sets it aside from the other damsel-in-distress stories, is that the women get away from the men for better or for worse whereas nearly every other fairy tale ending includes the male lead’s return. Faber’s ability to create a personality for his female characters adds a depth that is valuable to women everywhere. "I’m glad you chose me, even so; I hope I satisfied all of your desires, or at least showed you a good time." - Faber, The Crimson Petal and the White, pg. 895.

0 Comments

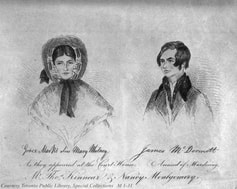

A socio-political commentary on gender and war, Alasdair Gray’s Poor Things brings the Victorian era to its knees and asks it, “Why?” The novel is centered around a young woman who is somewhat brought back to life, in a Frankensteinian-type of way. Having the body of a young woman, but the brain of a child, Bella Baxter is a monster. However, it is not because of her being pieced together without consent by a man who felt the godly need to insert himself into her life. It is because she is a woman. Gray’s novel is set up in a way that is unlike anything else I have ever read. The introduction prepares readers for what is to come as most do. Though, I do not think most will be able to understand the true depth of this warning until they complete the novel. Gray writes, “... readers who know nothing about the daringly experimental history of Scottish medicine will perhaps mistake it for a grotesque fiction. Those who examine the proofs given at the end of this introduction will not doubt that… a surgical genius used human remains to create a twenty-five-year-old-woman” (VII). Initially, the meaning of these lines does seem quite clear. Readers of Poor Things are expected to doubt the probability that a grown woman was reborn to men. However, upon completion of the novel, readers may recognize a second meaning to this warning. It is entirely possible that Gray was commenting on the unfortunate true fact that women often are reborn to men within society. The beginning of Gray’s novel easily reads like fiction as it focuses on the chilling creation of Bella Baxter. “I was called to examine the body you know as Bella… Geddes saw a young woman climb onto the parapet of the suspension bridge near his home. She did not jump feet first like most suicides. She dived clean under, like a swimmer but expelling the air from her lungs, not drawing it in, for she did not return to the surface alive” (32). This passage alone reflects both contexts of the message that Gray leaves readers in the introduction early on. While it is possible that these lines are simple plot narration, it is equally possible that Gray is commenting on the way in which women have historically had no say in how to dictate their own lives. Bella, for reasons unknown to the reader, was in control of her life the day that she decided to leave it behind. Though she may not have had any say in the dreadful manner in which she arrived at this tragic decision, she was able to put an end to it. Sometimes, that is all anyone wants. For Godwin Baxter to believe that he knew what Bella needed reflects the indirect play on words regarding his nickname, God. He made a decision that was not his to make, as many men of a certain stature have throughout history for more than just the women of certain communities, but for everyone in them. As the novel progresses, this Feminist-focused discussion continues as readers observe Bella’s attempt to reject gender roles and political limitations. Personally, I believe that whether or not Bella (later known as Victoria) is successful in rejecting gender roles and political beliefs set onto her by those around her is not the key element at the heart of this novel. Instead, I believe it is the question of why women are still subject to a select group of elite men, or women who embrace the masculine roles of their cohort in order to establish themselves, making decisions for them. Why are these moments simply accepted for what they are instead of analyzed and adapted for the better? "’And that is why you should marry me, Bella. You will be my slave in law, but not in fact.’" - Gray, Poor Things, pg. 155.  With perception at its core, Barnes’ novel travels alongside an imprisoned man and a famous author attempting to help him earn his freedom. While additional themes of the novel include racial injustice, legal injustice, and faith are of equal importance and presence in this novel, equally deserving of attention is the possibility of Barnes’ play on words and the commentary it provides into Barnes’ own thoughts about perception. The novel shifts between two male leads, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and George Edalji. The former, though, offers an interesting play on words as he is Arthur the author of the incredible stories of the detective known as Sherlock Holmes. Arthur, the author, the creator of narratives and “palaces built out of paragraphs”1. Sir Arthur’s profession offers several interesting roads to travel. The first being that his job solely requires him to both create narratives and sell them. If an author publishes a story that is incapable of enticing an audience no matter how large or small, they surely are not a good one. While spinning yarns might be an admirable talent, consider this in connection with a legal case. Are men and women convicted off of a good story or evidence? Should the justice system be swayed by evidence or an enthralling theory? The American justice system is set up in a way that individuals should be considered innocent until proven guilty by a jury of their peers, who shall only convict them if they are without reasonable doubt. Whether Americans are tried fairly in this way, whether George was tried fairly in a similar way within America’s parent country, leads us to our next point about Barnes’ many interpretations of perception found in Sir Arthur’s name. To be an author goes beyond telling and selling a story. As mentioned, this blog is run by a Graduate student at Wright State University. In my own seminar class, two colleagues offered insight into what Arthur’s name could mean. Trey Brown offered that Arthur’s name-play is interesting in the way that an author sometimes knows the ending they wish to reach, and will create a narrative to assist them in reaching it. Sir Arthur decides immediately that George is innocent. He expresses that he not only thinks George is innocent, he “knows” George is (Barnes, 270). Brown’s insight suggests, in connection to a legal case, that it is highly likely an author might be missing evidence that does not fit the narrative they have decided on. When looking for things to prove George’s innocence, Sir Arthur negates what might prove George’s guilt (Barnes, 309). Another classmate, Kendra Fields, offers that because Sir Arthur is the author who created such a whimsically intelligent and astute detective, he is often perceived as an equally intelligent detective. This fictional credibility may transfer to the real members of the jury in a way that makes them eager to believe the same thing that Sir Arthur eagerly wants to prove. This, again, reflects the fragility of the legal system as people with influence are often able to sway cases one way or another without much evidence. These roads that map out the possible meaning of Sir Arthur’s name could reflect Barnes’ own awareness of the power in his profession, and thus his understanding of the power of perception. As an author, Barnes has the chance to wield the same power as Sir Arthur, the power to persuade others to buy into their own narrative. Barnes highlights not only the power of persuasion in literature but the power of persuasion in unjust legal systems. "’You will only see him with the eyes of faith.’" - Barnes, Arthur & George, pg. 325. 1. “Burn”, Hamilton, 2015  What’s in a name? What history? What life? What stories? Readers may have these questions after finishing Atwood’s brilliant novel, where these questions remain unanswered by the author to torture the reader. Or rather, at least, to inspire the reader to consider these questions and then some. Alias Grace follows the story of a convicted murderess with narration limited by the protagonist, Grace Marks. Upon completing the novel, readers may feel lost at sea with nothing to help them navigate their way home except the stars, a tool only the ancient experts are privy to. Grace is quite like these ancient navigators. She is deliberate in what knowledge she shares with whom. We never really know the truth. One element that is uncomfortably clear, though, is that the romanticism of murderers is a tale as old as time, where the beauty is the beast. Throughout Atwood’s work, Grace is consistently aware of how others perceive her, as well as how she wants to be perceived. Is she telling a carefully crafted story because she wants to get away with murder? Because she is insane? Or because she is in a world ruled by men and a woman who was in the wrong place at the wrong time? Grace’s interaction with the men of the novel screams, “Help me, I keep finding myself at the mercy of men who desperately miss their mothers.” Dr. Jordan, of course, is the first example of this. However, I would like to discuss Jaime Walsh, the man who testified against Grace during her trial but eventually married her when she was pardoned. Jaime forces Grace to relive her miserable life often, sparing no gruesome details. Grace remarks that the more unsettling her stories are, the more “in ecstasies” he finds himself (Atwood, 457). Commonly, murderers and famous loons throughout history are doted on. Charles Manson and Ted Bundy make the cut in reality while Tate Langdon and Norman Bates carry the fictitious burden. While most who suffer from hybristophilia are guilty of romanticizing murderous men, Grace finds herself in an inverse position where Jaime is beside himself without Grace’s gory stories. Equally as strange as this fascination with the freaky things in life is Grace’s sense of pride when she manages to please her husband. He feebly begs her for forgiveness and upon receiving it, is thus put back into his manhood. As a woman, Grace has found power in a man’s world. The longer she can keep someone listening, the more she can forgive her husband. The stronger she feels while remaining a victim simultaneously. To think that a woman, convicted for murder for most her of her life, is still a victim to the men around her creates an uninteresting contrast. The restrictions of a woman’s uterus knows no bounds, as no matter what the situation Grace finds herself in she will be reduced to her womanhood. If Grace was mentally insane, she would be subject to ridicule for melodramatics or hysteria. If Grace was a murderer, she would again be subject to commentary with connotations of being emotionally overwhelmed. Lastly, and perhaps the worst-case scenario that Grace could possibly find herself in, Grace could find herself telling a story of feigned illness as she was simply in the wrong place at the wrong time… Caught by men, diagnosed by men, and thus having to play along in hopes that mercy would find her. What is in a name? A gender? An era? “The way I understand things, the Bible may have been thought out by God, but it was written down by men. And like everything men write down, such as the newspapers, they got the main story right but some of the details wrong.” - Atwood, Alias Grace, pg. 459.  It seems fit for the first post of The Neo-Victorian Faux Historian to be in regards to a novel centered around modern scholars solving mysteries, or attempting to. The typical elements that drive Neo-Victorian novels such as desire, history, truth, and romance are all present. However, the most intriguing sentiment of the novel comes early on… Roland, the scholarly protagonist, is seen stealing letters that he hopes will lead him to a massive discovery. It would seem that Roland finds it appropriate to steal the letters so that he is not only the first to make whatever discovery awaits, but that he and he alone is worthy of it. For centuries, written documents have left a trail that allows contemporary folk like you and I to travel backwards. What comes with us, though, when we travel backwards? What comes out of a young Graduate student of English travelling back to Shakespeare’s time to interpret The Taming of the Shrew? A modern scientist will look back on the discovery of mankind’s anatomy and have what criticisms or take what for granted, as the modern scientist holds the most accurate knowledge already? There are many schools of thought on how to interpret writing from the past, what to consider about the author when reading such literature, or whether to throw out the author (and possibly their work) entirely. I find myself interpreting life through the lens of a Post-Modernist and yet, whenever a novel opens before me, a Modernist breathes from within. In analyzing Roland’s actions of stealing those letters as a Modernist, I find myself focusing on the symbolism, the metaphor… Theft is surely created out of necessity. What need did Roland have? The desire for knowledge? Fame? Theft also occurs out of a feeling that someone is owed something, that they should take it for themselves at whatever cost. To be an individual with such thoughts that occur in a library, no doubt, an archive for all implies a blatant disregard for others. Is this echoed elsewhere in Roland’s life? I’ll not spoil too much in case you take it upon yourself to read Byatt’s work, though I will give you a hint to consider Roland’s romantic life. Roland’s action is a minor one in the sense that it is grazed over, though it is arguably of major significance. It allows for an illustration of what someone brings with them when reading a text that came from the past. Roland’s theft shows his motivation in reading and what biases might arise. If one were to read something with hopes of fame or a large discovery awaiting them, would letters not read juicier? Would landscape paintings not cry to be more than water and trees? As a Graduate student who is taking a Neo-Victorian novel course in hopes that it provides her more tools to make her successful in analyzing Gothic Literature and Film, I can assure you… When I read literature from the past, or am given an assignment, I am never taking it at face value. I am always looking for a useful tool to add to my collection. "These superfluous adjectives were the traces of his own views, and therefore unnecessary." - Byatt, Possession, pg. 325. |

About the Faux HistorianAs a Graduate student at Wright State University, Kayelynne Harrison found herself studying Neo-Victorian Literature as she pursued her Master of Art's Degree in ENG: Literature. This page is a small reflection of the work she has accomplished in her last semester. Though preferring to study Gothic Literature and Horror Film analysis, where she hopes her future lies, these Neo-Victorian studies prove helpful in Kayelynne's journey. Archives

April 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed